Title: I Learned Computer Architecture The Hard Way So You Dont Have To

—

**Title: I Learned Computer Architecture The Hard Way So You Dont Have To**

**(Intro)**

I once stared at a diagram of a CPU and felt… nothing. It was just a bunch of boxes and lines. I saw acronyms like ALU, CU, MAR, and MDR, and they felt like a secret code I was never meant to crack. I’m not kidding, I spent months, maybe even years, buried in dense textbooks trying to understand how a computer *actually* works, and it was brutal. The language was impenetrable, the diagrams were confusing, and every time I thought I finally got it, the next page would introduce five new exceptions and a dozen more acronyms that sent me spiraling right back to square one.

But all that struggle, all those late nights wrestling with data paths and control signals, led to one single ‘aha!’ moment. A moment where the fog just… cleared. And all those complex pieces clicked into place with a simple, powerful analogy. This video is the cheat sheet I wish I had back then. I’m going to save you the headache and the frustration. I’m going to give you that ‘aha!’ moment right now, and it all starts with a magic kitchen.

**(Section 1: The Magic Kitchen – Your New Mental Model)**

Forget the boxes, forget the jargon. For the rest of this video, I just want you to imagine a kitchen. But this isn’t your kitchen. It’s a hyper-efficient, magical kitchen where a master chef works nonstop. This kitchen *is* our computer, and if you can understand how it runs, you can understand all of computer architecture.

So, who’s the star of any kitchen? The chef.

In our magic kitchen, the Chef is the **Central Processing Unit**, or **CPU**. This is the brain of the whole operation. The Chef reads the recipes and does all the actual work—the chopping, the mixing, the sautéing—to create the final dish. He’s the engine, the one making everything happen. Everything else in this kitchen exists just to help him.

Of course, a chef is useless without recipes. In our kitchen, the recipes are **software**. An app, a video game, a web browser—it’s all just a very detailed recipe book. Each line of code is a single step. “Add two cups of flour.” “Whisk until smooth.” “Preheat oven to 350.” These are the instructions our Chef, the CPU, is going to follow.

But where does the Chef work? You don’t cook on the floor. You need a workspace. In our kitchen, that’s the countertop. The countertop is your computer’s **Random Access Memory**, or **RAM**.

The countertop is the Chef’s immediate-access work area. It’s where he lays out the ingredients he needs *right now* and the specific recipe page he’s working on. The key thing about the countertop—our RAM—is that it’s fast and right there. The Chef can grab anything he needs in an instant. The trade-off? The countertop has limited space. You can’t put every ingredient you own on it at once. And crucially, when the kitchen closes and the lights go out, the countertop is wiped clean. Everything left on it is gone. This is what’s known as **volatile** memory. It only works when the power is on.

So, if nothing stays on the countertop, where are the ingredients and recipes stored? In the pantry and the refrigerator. This is your computer’s **storage**, like a **Hard Disk Drive (HDD)** or a **Solid-State Drive (SSD)**.

The pantry is where you keep everything permanently. All your recipe books, spices, and canned goods. It’s huge. You can store a ton of stuff in there. And when the power goes out, everything in the pantry is still there the next day. It’s **non-volatile**. But here’s the catch: the pantry is way across the room. To get something, the Chef has to stop what he’s doing, walk over, find the item, and bring it back to the countertop. It’s much, much slower than grabbing something that’s already laid out for him.

This is the core relationship between your CPU, RAM, and Storage. When you “open a program,” you’re really just telling the Chef to go to the pantry (your SSD), grab a recipe book (the program) and its ingredients (the data), and put them on the countertop (RAM) to start cooking. The Chef (CPU) then works exclusively from that countertop because it’s so incredibly fast.

Finally, how does anything get around this kitchen? How do ingredients get from the pantry to the countertop? How does the finished dish get served? This is where the tireless kitchen helpers come in. These helpers are the **Buses** in your computer.

Buses are just the communication pathways connecting everything. Think of our helpers as a team with three specific jobs, matching the three main types of buses:

1. The **Address Bus**: This helper doesn’t carry a thing. Their only job is to communicate *locations*. The Chef says, “I need the sugar,” and the Address Bus helper runs to the pantry and points to the exact shelf where the sugar is. They carry the *address* of the data.

2. The **Data Bus**: This helper is the muscle. Once the Address Bus helper points to the sugar, the Data Bus helper goes to that spot, picks it up, and carries it back to the Chef’s countertop. They move the actual *data*.

3. The **Control Bus**: This helper is the manager, shouting out commands and making sure everything is synchronized. They carry signals from the Chef, yelling things like “READ from the pantry now!” or “WRITE this to the countertop!” They prevent chaos and make sure data is fetched or stored at exactly the right time.

So, let’s recap our kitchen: The **CPU** is the Chef. **Software** is the recipe. **RAM** is the fast, temporary countertop. **Storage** is the slow, permanent pantry. And the **Buses** are the helpers moving everything around.

This one analogy, this kitchen, was my ‘aha!’ moment. It turned all those abstract diagrams into a living system I could finally wrap my head around.

**(Section 2: The Kitchen’s Blueprint – Von Neumann Architecture)**

Now that we have our kitchen, let’s talk about its layout. Most computers today, and our magic kitchen, are designed using a concept from 1945 by the brilliant John von Neumann. It’s called the **Von Neumann architecture**.

His most important idea was the **stored-program concept**. Before this, computers were basically built for a single purpose. To change that purpose, you had to physically rewire them. It’d be like having a kitchen that could only make toast. If you wanted soup, you’d have to literally tear out the toaster and install a stove. It was unbelievably inefficient.

Von Neumann’s genius was to ask: what if the recipe (the instructions) and the ingredients (the data) were stored in the same place? What if they were both just… information?

In our kitchen, this means the recipe books and the ingredients are both stored in the pantry and brought to the countertop together. That’s the core of the Von Neumann architecture, which has four main parts: a CPU (our Chef), a single memory system (our countertop-and-pantry), input/output (like a waiter taking an order or serving a dish), and the buses (our helpers) connecting it all.

This design is beautifully flexible. You can make any dish just by grabbing the right recipe. But it also creates a famous problem, a traffic jam that still plagues computer designers today: the **Von Neumann Bottleneck**.

Think about it. Our Chef is incredibly fast. He can chop an onion in a fraction of a second. But he’s always waiting. He’s waiting for his one helper (the Data Bus) to run to the countertop, fetch one ingredient, bring it back, then run back for the next one. The Chef can work way faster than the data can be delivered to him. That single path between the Chef (CPU) and the countertop (Memory), which has to carry both recipe steps *and* ingredients, becomes a massive bottleneck. The entire kitchen’s performance isn’t limited by the Chef’s speed, but by the speed of that one pathway.

We’ll get back to how modern kitchens try to solve this. But first, we need to zoom in on the Chef himself. What is he actually *doing* all day? It turns out, he’s just repeating a simple, three-step dance, over and over.

**(Section 3: The Chef’s Workflow – The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle)**

Everything your computer does—from moving your mouse to rendering a 3D world in a game—is just the CPU performing the **Fetch-Decode-Execute cycle** billions of times per second. It is the fundamental rhythm of computing.

Let’s break down this dance, step-by-step, using our kitchen and introducing a few of the Chef’s personal tools, which are the **registers** inside the CPU. Registers are like the Chef’s hands or tiny pockets—unbelievably fast but extremely small storage spots right on his person.

**Step 1: Fetch**

The cycle begins. The Chef needs his next instruction.

To do this, he checks a little notepad in his pocket called the **Program Counter (PC)**. The Program Counter always holds the memory address of the next instruction in the recipe. Let’s say it points to “Page 5, Line 3” on the countertop.

The Chef (or more specifically, his internal manager, the **Control Unit** or **CU**) needs to get that line. He gives the location from his Program Counter to his Address Bus helper. That address is temporarily jotted down on a sticky note, the **Memory Address Register (MAR)**.

Now the Control Bus helper yells “READ!” The instruction at that location—let’s say, “Chop two carrots”—is picked up by the Data Bus helper. The helper carries it back to the Chef.

The Chef takes the instruction and puts it on a small clipboard right in front of him called the **Current Instruction Register (CIR)**. This clipboard holds only the single instruction he’s working on *right now*.

Finally, before he moves on, he updates his Program Counter to point to the *next* instruction, “Page 5, Line 4,” so he’s ready for the next cycle. The Fetch stage is done.

**Step 2: Decode**

The Chef looks at the instruction on his clipboard (the CIR): “Chop two carrots.” Now he has to figure out what that actually means. This is the Decode step.

His **Control Unit (CU)** is the part of his brain that interprets the command. Its circuitry is wired to recognize “Chop.” It understands this requires the chopping station, and it sees the other details: “two” and “carrots.” The CU now knows exactly what to do and prepares all the internal signals to get it done.

**Step 3: Execute**

This is where the magic happens. The Control Unit issues the commands to the part of the Chef that does the physical work. In a CPU, this is the **Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU)**.

The ALU is the mathematical and logical engine of the CPU. It handles addition, subtraction, multiplication, and logical tests like AND, OR, and NOT. In our kitchen, it’s the part of the Chef that does the actual chopping, mixing, and heating.

The CU directs the ALU to get the data—the carrots. This might involve another quick fetch from the countertop, placing the carrots in a temporary holding bay called the **Memory Data Register (MDR)**.

The CU then activates the ALU. The ALU takes the carrots and performs the “chop” operation. The result—the chopped carrots—might get stored in a special workbench register called the **Accumulator (ACC)**, which is just a default spot to hold the results of recent calculations.

And that’s it. The instruction is executed. The carrots are chopped. The cycle is complete.

What happens next? Back to Step 1: Fetch. The Chef looks at his Program Counter, which now points to “Page 5, Line 4,” and starts the whole process over again for the next instruction.

Fetch. Decode. Execute. Billions of times per second. That is the heartbeat of your computer. Every complex thing you see on screen is an illusion, built on this relentlessly simple cycle.

**(Section 4: The Professional Kitchen – Advanced Concepts)**

Okay, so far we’ve built a basic home kitchen. It works. But it’s not winning any Michelin stars. To understand modern computers, we need to upgrade our kitchen to a professional, state-of-the-art restaurant. This is where we get into the clever tricks that make today’s processors so fast.

**Different Cooking Philosophies: CISC vs. RISC**

As kitchens got more serious, two big philosophies emerged on how to design a Chef’s skillset. This is the world of the **Instruction Set Architecture (ISA)**—the dictionary of commands a CPU understands.

First, you have **CISC**, or **Complex Instruction Set Computing**. A CISC Chef is like a classically trained, old-school chef. His recipe book has incredibly powerful instructions. A single step might say, “Prepare Coq au Vin,” and he automatically knows the dozens of sub-tasks involved. The upside is your recipes (programs) can be very short. The downside is the Chef’s brain has to be enormously complex and, because the commands are so involved, can be slower to execute. Early Intel x86 processors were classic CISC chefs.

The other philosophy is **RISC**, for **Reduced Instruction Set Computing**. A RISC Chef is a modern line cook. He only knows a few, very simple, highly optimized commands: “Chop.” “Sear.” “Slice.” “Mix.” Each command does one tiny thing, but he does it with lightning speed. The recipe to make Coq au Vin will be much longer, but because each step is so simple and fast, the total time can actually be shorter. The Chef’s brain is simpler, smaller, and more energy-efficient. This is the philosophy behind the ARM architecture, which is the foundation Apple used to build its custom M1, M2, and M3 chips and powers nearly every smartphone on Earth. The whole industry has been moving towards the RISC philosophy because it’s just so fast and efficient.

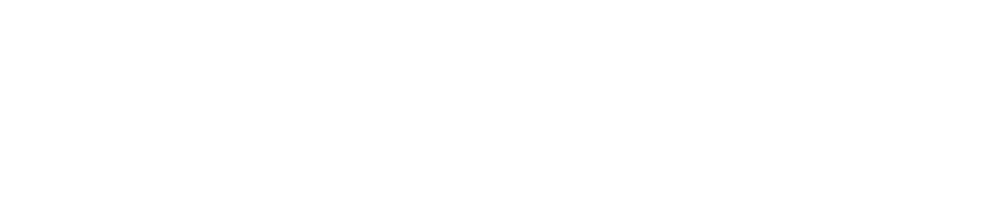

**Optimizing the Workspace: The Memory Hierarchy**

Remember our biggest problem? The Von Neumann bottleneck. The Chef is always waiting for ingredients. Professional kitchens solve this with a **memory hierarchy**.

Imagine the Chef has levels of storage, each faster and closer than the last.

1. **Level 0: Chef’s Pockets (Registers)**. We met these. The absolute fastest. The ingredient is literally in his hand. But space is extremely limited.

2. **Level 1: The Spice Rack (L1 Cache)**. A tiny rack right next to the Chef. It holds only the most common things: salt, pepper, oil. Accessing it is almost instant. This is a tiny, super-fast memory bank built right into the CPU core.

3. **Level 2: The Mini-Fridge (L2 Cache)**. Under the Chef’s workstation. A bit bigger than the spice rack, slightly slower, but still crazy fast. It holds pre-chopped veggies and sauces for the current service. This is another memory bank, larger than L1, right next to the core.

4. **Level 3: The Prep Counter (L3 Cache)**. A larger, shared prep area for a few chefs working together. Bigger still, a tad slower, but it’s a huge cache of common ingredients multiple chefs (or cores) might need. L3 cache is often shared across all cores on a CPU.

5. **Level 4: The Main Countertop (RAM)**. Our main workspace. It’s big, but walking over to it takes time, so it’s way slower than any cache.

6. **Level 5: The Walk-in Pantry (Storage)**. Our SSD. It’s enormous, but a trip here is a major time-sink.

When the Chef needs a tomato, he first checks his pockets (registers). Nope. He glances at his spice rack (L1 cache). Not there. He checks his mini-fridge (L2 cache). Ah! There it is. That’s a **cache hit**. Super fast.

But what if he needs a rare spice? He checks pockets, L1, L2, L3… nothing. He has to stop and send a helper all the way to the main countertop (RAM). That’s a **cache miss**, and it’s a huge performance penalty. If it’s not even on the countertop, the helper has to make the long journey to the pantry (storage), which is an even bigger delay. Clever algorithms are always trying to predict what the Chef will need next and move it up the hierarchy, from the slow pantry to the fast caches.

**Making the Kitchen More Efficient: Pipelining, Superscalar, and Multicore**

Okay, the workspace is optimized. How do we make the Chef himself faster?

One big breakthrough was **Pipelining**. In our simple kitchen, the Chef does all three steps—Fetch, Decode, Execute—for one instruction before starting the next. This is inefficient. While he’s chopping carrots, the parts of his brain for fetching and decoding are just sitting idle. Pipelining creates an assembly line.

* One specialist Chef only does **Fetching**.

* He hands the instruction off to a **Decode** specialist.

* The Decode specialist hands it off to an **Execute** specialist for the actual chopping.

Now, while one instruction is being executed, the next one is being decoded, and the one after that is being fetched. Three instructions are being worked on at once, just in different stages. This massively increases the kitchen’s **throughput**.

But why stop there? What if our Execute Chef has two sets of hands? That’s **Superscalar Architecture**. A superscalar processor has multiple execution units. It’s a chef who can chop vegetables and stir a pot at the same time. If the CPU gets two instructions that don’t depend on each other (like “Chop Carrots” and “Measure Flour”), it can execute them both in parallel, in the same cycle.

The most visible innovation, though, is **Multicore Processors**. Pipelining and superscalar are about making one Chef faster. Multicore is simpler: we just build more kitchens.

A dual-core CPU is like having two full Chefs, each with their own personal L1/L2 caches, working side-by-side. A quad-core CPU is four chefs. An 8-core CPU is eight chefs. They might share a large L3 cache and the main RAM, but they can work on totally different recipes (or threads) at the same time. This is why your computer can play a video, run a virus scan, and let you browse the web all at once. The operating system acts as the head chef, assigning different tasks to all the available Chefs (cores).

**(Conclusion: The Cheat Sheet Unlocked)**

So, let’s step back from the kitchen. We started with a mess of boxes and lines. But now, you have the cheat sheet.

You know the **CPU** is the Chef. You know **RAM** is the fast countertop and **Storage** is the slow pantry. You know **Buses** are the helpers running around with addresses and data.

You get the blueprint for almost every computer, the **Von Neumann architecture**, and its built-in traffic jam, the **Von Neumann Bottleneck**. You know the heartbeat of computing is the **Fetch-Decode-Execute cycle**, a simple dance repeated billions of times a second.

And you’ve seen the pro upgrades. How **RISC** and **CISC** are different cooking philosophies. How the **memory hierarchy** of caches—the spice racks and mini-fridges—is a brilliant hack to keep the Chef from waiting. And how real speed today comes from assembly lines (**pipelining**), extra hands (**superscalar**), and more kitchens (**multicore**).

I spent years trying to connect these dots. The difference for me was finding an analogy that made the abstract concrete. The kitchen is what made it all click.

And now you have it. You didn’t have to learn it the hard way. The next time you see a new processor announced with more cores, or a bigger cache, you’ll know what that actually means. You’ll picture a bustling kitchen, getting more chefs and bigger spice racks. You now have a solid, intuitive way to understand the very heart of the tech that runs our modern world.

**(CTA – Call to Action)**

If this video helped clear things up for you, consider subscribing. We’ve demystified the CPU, but there’s a whole different beast in the GPU—the specialized artist of the computer world. Let me know in the comments if you want the “magic kitchen” explanation for how a GPU works. Thanks for watching.